A 21st-Century Map for a 20th-Century Discovery

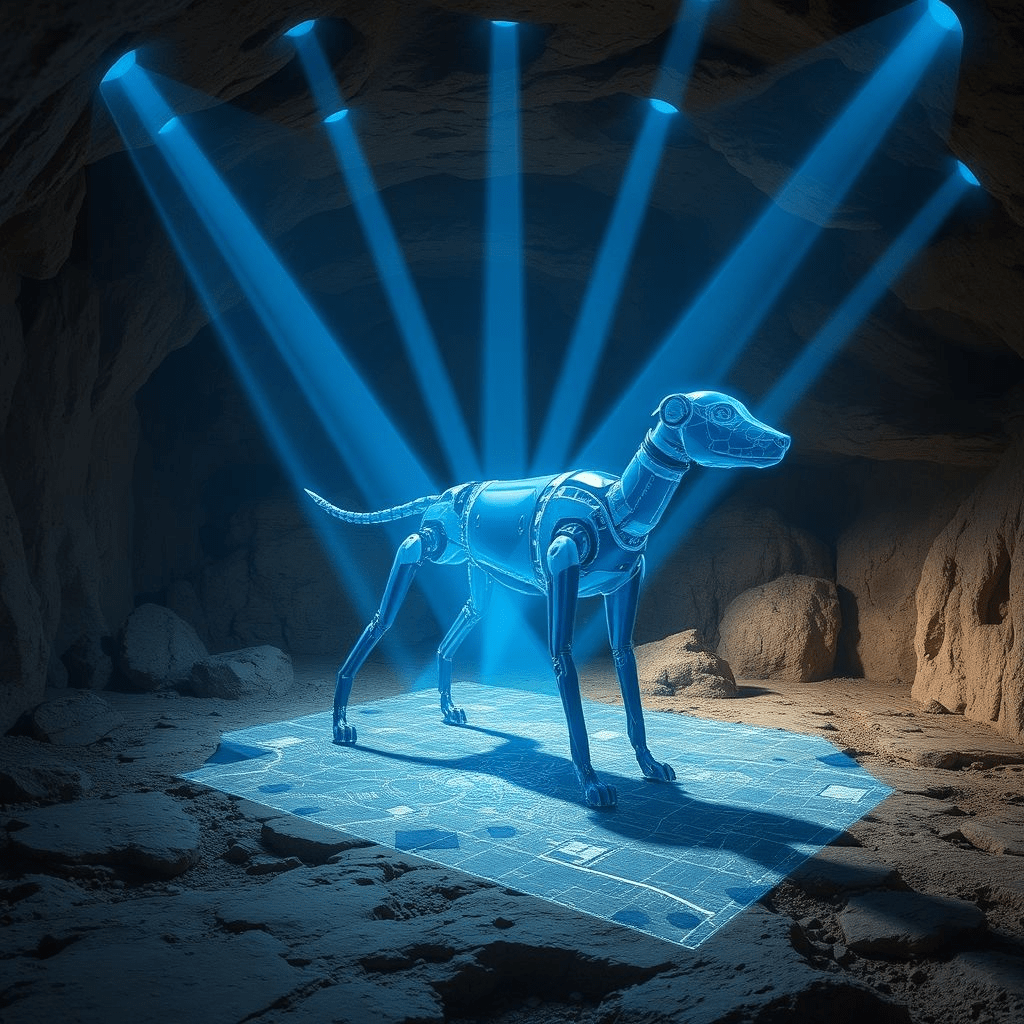

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has completed a high-resolution Inner Space Cavern digital twin, fusing advanced LiDAR scanning with a robotic “dog” to capture precise geometry of the Central Texas cave—over six decades after it was first uncovered during highway drilling in 1963. The newest mapping push, carried out across four months and 18 field days, produced a detailed 3D model spanning 5.5 miles of chambers and passages. The effort was publicly highlighted in fresh coverage this week, underscoring both its conservation and infrastructure-planning value.

Why Map the Cavern Now?

Inner Space Cavern lies beneath the I-35 corridor near Georgetown, an area experiencing sustained population and construction growth. Accurate subterranean data helps transportation planners understand where voids, delicate formations, and hydrologic pathways exist relative to surface infrastructure. TxDOT says the digital twin strengthens “spatial awareness” between cave volumes and the surface above—critical for long-term safety, environmental stewardship, and future construction decisions.

How the Tech Worked

LiDAR (light detection and ranging) emits rapid pulses of light and measures their return, producing dense point clouds that can be meshed into accurate 3D models. TxDOT’s team combined traditional survey workflows with mobile and tripod-mounted LiDAR to handle large chambers and constrained passages. A notable addition was “Dot,” a dog-shaped robot that carried scanning payloads into tricky or hazardous sections—areas where footing is unstable, ceilings are low, or human disturbance must be minimized. TxDOT previously profiled “Dot” and the workflow as part of a “once-in-a-lifetime survey,” detailing how the robot can be outfitted with inspection and survey equipment to extend coverage safely.

Protecting Bats—and Visitors—While Scanning

Because Inner Space Cavern is both a living cave ecosystem and a tourist attraction, the survey schedule was restricted to three days per week to limit disruption. Teams contended with high humidity, poor visibility, and delicate speleothems; conservation protocols shaped where and how scanners could be deployed. Field operations coordinated around tri-colored bat activity and public tours to keep the project low-impact. The newly surfaced report details these constraints and the methodical approach the team used to capture clean data sets without disturbing wildlife or visitors.

Deliverables: From Point Clouds to Planning-Grade Models

The Inner Space Cavern digital twin is more than a static visualization. By tying cave dimensions to surface coordinates, engineers can analyze potential interactions between karst features and roadways, run simulations, and plan mitigation for sinkholes or groundwater pathways. TxDOT’s information technology specialists contributed to CAD workflows, survey integration, and mapping support—turning LiDAR data into assets planners can use for decades as Central Texas grows.

A Brief History: From Accident to Asset

Inner Space Cavern was famously discovered in 1963 when transportation crews drilling for a highway bridge broke into an underground void. Since then, the cave has become a regional attraction and a geological archive of ancient fauna and climate signals. Modern mapping now closes a loop, transforming a mid-century accident into a 21st-century digital resource to protect both the cave and the infrastructure above it.

Public Interest—and Robotics Buzz

The story has resonated widely beyond the transportation community, with engineering and reality-capture groups amplifying TxDOT’s use of robotics and LiDAR underground. Posts and recaps have spotlighted the unusual pairing of highway survey teams with speleology, and the creative use of a robot dog to safely extend coverage. Though those mentions surfaced over recent weeks, they help contextualize this week’s renewed attention.

What Experts Are Saying

Cave conservation advocates generally welcome high-fidelity models that reduce human impact. Transportation engineers point to the operational benefits: “digital twins” make it easier to brief stakeholders, plan future work, and monitor changes over time. As TxDOT described it, the cavern survey was a rare chance to combine inspection, environmental stewardship, and engineering in one effort—“once-in-a-lifetime,” in the agency’s words. (Short quote from TxDOT materials.)

What Comes Next

With the Inner Space Cavern digital twin complete, TxDOT can overlay hydrologic data, model subsurface drainage during heavy rain events, and test “what-if” scenarios for future I-35 improvements. Researchers and educators may also leverage the twin for virtual tours or classroom lessons that bring the underground world above ground—without increasing foot traffic in sensitive zones.

Bottom line: The project shows how robotics and LiDAR can preserve fragile environments while giving planners the precision data they need. In a region where mobility and growth are inseparable, mapping what’s beneath the pavement may prove as important as what’s on top.